Spring is in the air, planting season is in progress, but what does Mother Nature have in store?

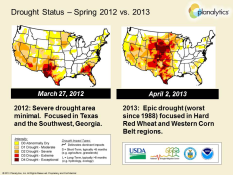

“We are experiencing the worse drought since 1988 (and reminiscent of the 1930’s) in terms of coverage,” states Jeffrey Doran, Senior Business Meteorologist, Planalytics, Inc. Most of that area consists of the Great Plains region and the southwestern United States.

“Coming into the winter months, there was a better moisture profile than the year before, but deficits are so great that drought conditions prevail,” says Doran. Even with the moisture gained in February and March, many areas are still one to four inches below average precipitation for the period, and six to ten inches overall. There is real concern over the snow pack in Southwest Colorado and Northwest New Mexico where moisture levels are 20% to 60% below normal. “The effects of the drought from the last few years is still causing issues,” Doran emphasizes.

“Looking at macro factors influencing weather, the fact that the equatorial Pacific is in a neutral state (neither El Niño warm phase nor La Niña cool phase) is an important consideration,” explains Doran. With that being said, there are much cooler waters than typical in the eastern mid-latitudes of the Pacific Ocean. When reviewing historical patterns, cooler waters in this region also known as the negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation, means more frequent La Niña conditions which tend to last longer. La Niña patterns typically mean very extreme conditions during the U.S. growing season. The past 2 growing seasons were ones dominated by La Niña conditions and in large part responsible for the significant drought. That drought began in 2011with the worst seen in Texas and Oklahoma since the 1950s. While Planalytics expected another droughty year last year, no one could have predicted how extreme and vast the drought would spread (see Map #1). As long as we continue to have a cold Pacific basin, there will likely be more years of extreme conditions to include increased tropical storms, drought and heat. An El Niño pattern typically is needed to break this drought cycle does not appear imminent. “At this time, there is nothing showing a transition to an El Niño pattern so we will likely remain in some level of drought for most growing areas,” says Doran. The one factor to keep an eye on is the solar activity. The sun will reach another solar maximum in 2013. That is important because history shows that this is followed by an El Niño event within 2 years, so possible relief is in sight and also a little hope for change.

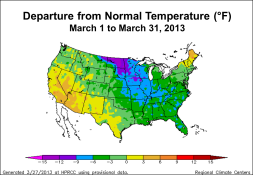

March 2012 was the warmest March across the US in history. There were a record number of tornados and severe weather episodes last March due to the warm weather. The warm spring also led to a quick transition to an extremely hot summer.

Spring 2013 to date is shaping up differently which is a good sign. The temperatures have been much cooler, and many areas have had significantly more moisture than last spring. Severe weather has been limited this year due to March 2013 being one of the coldest March’s in the past 50 years (see Map #2). Texas, Oklahoma, and Southern Kansas averaged 5-8 degrees below normal while Northern Kansas and Nebraska averaged 13+ degrees colder.

As we progress into late spring and early summer, severe weather is expected to become more active and widespread. An ENSO (El Niño-Southern Oscillation) neutral pattern usually brings an active storm season, and as temperatures warm up, the chance of severe weather increases to include large hail, strong winds, and tornadoes. Later in the growing season, it is also anticipated that tropical cyclones could target Texas and eastern portions of Oklahoma and Kansas. “We experience 11-14 named storms a year on average, but this year should have more,” Doran predicts. “More tropical cyclonesin the Western Gulf of Mexico may mean more moisture for the Plains region. From mid-August through mid-September, there is potential for much needed moisture coming to Texas and north into Kansas,” continues Doran.

Because of the winter and spring precipitation, topsoil moisture across the High Plains has been favorable for the planting season. “In the short term, there appears to be adequate moisture for planting and improved moisture profiles for emergence, but once into the primary growing season expect the moisture to dry up and temperatures turn hot,” warns Doran. “A virtual repeat of last year’s conditions is possible in many areas. Producers should be advised to select drought-resistance varieties and manage their crops for a dry scenario,” he adds.

Doran says the million dollar question is, “Will it be as hot as 2012?” Although the answer remains to be seen, there is a good likelihood of having a similar summer scenario as last year impacting corn and soybean pollination. The winter wheat crop should have relatively more moisture to work with, although yields may still be below trend. Any long term relief to the drought plaguing the High Plains and Southwest does not appear a high confidence scenario.

On the other hand, areas east of the Mississippi River including much of the Corn Belt Region are so saturated that producers are not sure when they will be able to get their crops planted. Late planting seems a foregone conclusion.

“Overall, there are very few places ideal for crops – drought or excessively wet conditions prevail,” concludes Doran. The only certainty is this will be another interesting, challenging year for production agriculture.

Feature Photo by: CraneStation, Drought Stressed Corn013, Flickr, http://www.flickr.com/photos/70377872@N04/7640125768/